<div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Astronomers in </span><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/australia" rel="" target="" title="Australia"><span>Australia</span></a><span> picked up a strange radio signal in June 2024, one near our planet and so powerful that, for a moment, it outshone everything else in the sky.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>The ensuing search for its source has sparked new questions around the growing problem of debris in Earth's orbit.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>At first, though, the researchers thought they were observing something exotic.</span></div></div><div><div id="adspot-mobile-medium"></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><strong><span>READ MORE:</span></strong><span> </span><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/national/east-coast-low-fears-of-bomb-cyclone-sydney-nsw-coast/058a06e0-ee22-472d-acd8-79afe1046280" target="_blank"><strong><span>Millions on alert as 'dangerous' storm ramps up flood fears</span></strong></a></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We got all excited, thinking we had discovered an unknown object in the vicinity of the Earth," Clancy James, an associate professor at Curtin University's Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy in Western Australia, said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>The data James and his colleagues were looking at came from the ASKAP radio telescope, an array of 36 dish antennas in Wajarri Yamaji Country, each about three stories tall.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Normally, the team would be searching the data for a type of signal called a "fast radio burst" — a flash of energy blasting forth from distant galaxies.</span></div></div><div><div class="OUTBRAIN" data-reactroot="" data-src="//www.9news.com.au/national/long-dead-satellite-emits-strong-radio-signal-puzzling-astronomers/da6b0421-13ce-4f6a-891e-1f6b69b7b081" data-widget-id="AR_5"></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"These are incredibly powerful explosions in radio (waves) that last about a millisecond," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><strong><span>READ MORE:</span></strong><span> </span><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/national/sydney-construction-manager-facing-deportation-after-ms-diagnosis/fde1ef5e-90b8-4211-b683-bcab115a68ab" target="_blank"><strong><span>Sydney construction manager facing deportation after health diagnosis</span></strong></a></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We don't know what's producing them, and we're trying to find out, because they really challenge known physics, they're so bright.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We're also trying to use them to study the distribution of matter in the universe."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Astronomers believe these bursts may come from magnetars, according to James.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>These objects are very dense remnants of dead stars with powerful magnetic fields.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"Magnetars are utterly, utterly insane," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"They're the most extreme things you can get in the universe before something turns into a black hole."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>But the signal seemed to be coming from very close to Earth, so close that it couldn't be an astronomical object.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We were able to work out it came from about 4500 kilometres away," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"And we got a pretty exact match for this old satellite called Relay 2, there are databases that you can look up to work out where any given satellite should be, and there were no other satellites anywhere near.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We were all kind of disappointed at that, but we thought, 'Hang on a second. What actually produced this anyway?'"</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><h3><strong><span>A massive short-circuit</span></strong></h3></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>NASA launched Relay 2, an experimental communications satellite, into orbit in 1964.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>It was an updated version of Relay 1, which lifted off two years earlier and was used to relay signals between the US and Europe and broadcast the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Just three years later, with its mission concluded and both of its main instruments out of order, Relay 2 had already turned into space junk.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>It has since been aimlessly orbiting our planet, until James and his colleagues linked it to the weird signal they detected last year.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>But could a dead satellite suddenly come back to life after decades of silence?</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>To try to answer that question, the astronomers wrote a paper on their analysis, set to publish on Monday in the journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>They realised the source of the signal wasn't a distant galactic anomaly, but something close by, when they saw that the image rendered by the telescope, a graphical representation of the data, was blurry.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"(T)he reason we were getting this blurred image was because (the source) was in the near field of the antenna, within a few tens of thousands of kilometres," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><strong><span>READ MORE:</span></strong><span> </span><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/national/minimum-wage-paid-parental-leave-superannuation-everything-changing-for-australians-july-one-explained/499f957b-565b-4fe5-90d4-ce381ac3f664" target="_blank"><strong><span>Pay, parental leave, super: Everything that's changing today</span></strong></a></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"When you have a source that's close to the antenna, it arrives a bit later on the outer antennas, and it generates a curved wave front, as opposed to a flat one when it's really far away."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>This mismatch in the data between the different antennas caused the blur, so to remove it, the researchers eliminated the signal coming from the outer antennas to favour only the inner part of the telescope, which is spread out over about 5.9 square kilometres in the Australian outback.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"When we first detected it, it looked fairly weak. But when we zoomed in, it got brighter and brighter. The whole signal is about 30 nanoseconds, or 30 billionths of a second, but the main part is just about three nanoseconds, and that's actually at the limit of what our instrument can see," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"The signal was about 2000 or 3000 times brighter than all the other radio data our (instrument) detects — it was by far the brightest thing in the sky, by a factor of thousands."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>The researchers have two ideas on what could have caused such a powerful spark. </span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>The main culprit was likely a buildup of static electricity on the satellite's metal skin, which was suddenly released, James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"You start with a buildup of electrons on the surface of the spacecraft. The spacecraft starts charging up because of the build-up of electrons. And it keeps charging up until there's enough of a charge that it short-circuits some component of the spacecraft, and you get a sudden spark," he explained.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"It's exactly the same as when you rub your feet on the carpet and you then spark your friend with your finger."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>A less likely cause is the impact of a micrometeorite, a space rock no bigger than one millimetre in size: "A micrometeorite impacting a spacecraft (while) traveling at 20 kilometres per second or higher will basically turn the (resulting) debris from the impact into a plasma — an incredibly hot, dense gas," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"And this plasma can emit a short burst of radio waves."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>However, strict circumstances would need to come into play for this micrometeorite interaction to occur, suggesting there's a smaller chance it was the cause, according to the research.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We do know that (electrostatic) discharges can actually be quite common," James said.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"As far as humans are concerned, they're not dangerous at all. However, they absolutely can damage a spacecraft."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><h3><strong><span>A risk of confusion</span></strong></h3></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Because these discharges are difficult to monitor, James believes the radio signal event shows that ground-based radio observations could reveal "weird things happening to satellites" — and that researchers could employ a much cheaper, easier-to-build device to search for similar events, rather than the sprawling telescope they used.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>He also speculated that because Relay 2 was an early satellite, it might be that the materials it's made of are more prone to a buildup of static charge than modern satellites, which have been designed with this problem in mind.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>But the realisation that satellites can interfere with galactic observations also presents a challenge and adds to the list of threats posed by space junk.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Since the dawn of the Space Age, almost 22,000 satellites have reached orbit, and a little more than half are still functioning.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Over the decades, dead satellites have collided hundreds of times, creating a thick field of debris and spawning millions of tiny fragments that orbit at speeds of up to 28,968km/h.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"We are trying to see basically nanosecond bursts of stuff coming at us from the universe, and if satellites can produce this as well, then we're going to have to be really careful," James said, referring to the possibility of confusing satellite bursts with astronomical objects.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"As more and more satellites go up, that's going to make this kind of experiment more difficult."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><strong><span>READ MORE:</span></strong><span> </span><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/national/space-katherine-bennell-pegg-australias-first-female-astronaut/67ad376a-f7e3-440c-b367-fb4c3c4a320c" rel="" target="" title="'What else could be cooler?': How Katherine became Australia's first astronaut"><strong><span>'What else could be cooler?': How Katherine became Australia's first astronaut</span></strong></a></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>James and his team's analysis of this event is "comprehensive and sensible," according to James Cordes, Cornell University's George Feldstein Professor of Astronomy, who was not involved with the study.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"Given that the electrostatic discharge phenomenon has been known for a long time," he wrote in an email to CNN. </span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"I think their interpretation is probably right. I'm not sure that the micrometeoroid idea, pitched in the paper as an alternative, is mutually exclusive.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"The latter could trigger the former."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>Ralph Spencer, Professor Emeritus of Radio Astronomy at the University of Manchester in the UK, who was also not involved with the work, agrees that the proposed mechanism is feasible, noting that spark discharges from GPS satellites have been detected before.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>The study illustrates how astronomers must take care to not confuse radio bursts from astrophysical sources with electrostatic discharges or micrometeoroid bursts, both Cordes and Spencer pointed out.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"The results show that such narrow pulses from space may be more common than previously thought, and that careful analysis is needed to show that the radiation comes from stars and other astronomical objects rather than man-made objects close to the Earth," Spencer added in an email.</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><span>"New experiments now in development, such as the Square Kilometre array Low frequency array (SKA-Low) being built in Australia, will be able to shed light on this new effect."</span></div></div><div class="block-content"><div class="styles__Container-sc-1ylecsg-0 goULFa"><a href="https://www.9news.com.au/national/how-to-follow-9news-digital/29855bb1-ad3d-4c38-bc25-3cb52af1216f" target="_blank"><strong><em><span>DOWNLOAD THE 9NEWS APP</span></em></strong></a><strong><em><span>: Stay across all the latest in breaking news, sport, politics and the weather via our news app and get notifications sent straight to your smartphone. Available on the</span></em></strong><span> </span><a href="https://apps.apple.com/au/app/9news/id1010533727" target="_blank"><strong><em><span>Apple App Store</span></em></strong></a><span> </span><strong><em><span>and</span></em></strong><span> </span><a href="https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=nineNewsAlerts.nine.com&hl=en_AU&pli=1" target="_blank"><strong><em><span>Google Play</span></em></strong></a><strong><em><span>.</span></em></strong></div></div>

Strange radio signal sparks new questions about growing problem of debris in Earth's orbit

Leave A Reply

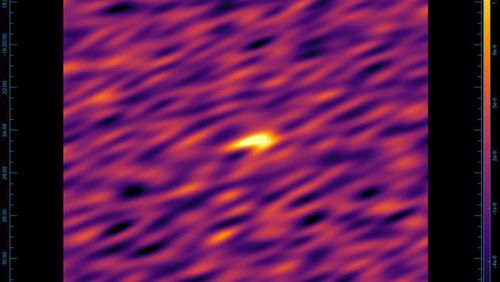

Your email address will not be published.*